One of the more complex, yet vital, forms of prosecutor-led diversion programming is one that addresses individuals that suffer from behavioral health needs. This tab was developed to assist program planners in addressing some of these complexities in their planning activities.

A behavioral health prosecutor-led diversion program provides prosecutors with unique benefits. Benefits include the opportunity to:

- divert individuals who have behavior health needs earlier in the criminal justice process

- accelerate their engagement with community-based treatment services

- reduce their collateral consequences of incarceration, such as the loss of housing, employment, and access to treatment services

- avoid the risks of their further mental health deterioration while in custody

- use criminal justice and behavioral health treatment resources in a more efficient and effective way

Such programs also help to destigmatize individuals suffering from behavioral health issues. Finally, behavioral health diversion provides the opportunities for investment in behavioral health services. One approach used in many states is “justice reinvestment.”

Providing meaningful behavioral health treatment to individuals while they are in custody can be challenging at best. But by developing early diversion mechanisms in partnership with treatment partners, law enforcement, and the defense, prosecutors can use a “new” criminal justice system “off- ramp” to redirect individuals to community-based treatment prior to the filing of formal charges or full engagement of the adversarial process.

Developing such a program does, however, present some unique challenges. First and foremost is the challenge of confronting the myth that individuals with mental illness are inherently more dangerousness and prone to violence than other defendants. For multiple reasons, some members of the public, some policy makers, and even some criminal justice practitioners believe that persons with behavioral health needs are at greater risk of committing violent acts in the future and thus need to be incarcerated.[1] Yet, a growing body of research establishes that such individuals are:

- no greater risk of committing future violence than other defendants[2],

- ten times more likely to be victims of crimes rather than perpetrators[3], and

- more likely to recidivate and experience greater behavioral health issues the longer they remain in custody.[4]

Other challenges include the need to:

- increase the rapidity of information sharing necessary to making sound decisions as early as possible

- identify appropriate community-based treatment services and a mechanism to pay for them

- contend with the challenges of providing assistance to individuals with co-occurring disorders, and

- navigating the complexities of HIPAA, privacy, and patient confidentiality.

For some examples of behavior health diversion programs, see:

Mental Health Advisory Board Report a Blueprint for Change

Centre County Behavioral and Mental Health Diversionary Initiative

For a detailed discussion of HIPAA and other privacy issues, see:

For strategies on funding programs, see:

Financing the Future of Local Initiatives

For a more detail discussion of the challenges of treating individuals with co-occurring disorders, see:

Substance Abuse Treatment for Adults in the Criminal Justice System. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 44, Pages 108-111, 137; and Improving Responses to People Who Have Co-occurring Mental Illnesses and Substance Use Disorders in Jails

Many of the issues connected with developing such a program are addressed under the general “Getting Started” tab of this website.

Here are additional things to think about in relation to developing a behavioral health prosecutor-led diversion program:

Program Goals

PLD Behavioral Health programs should be particularly attuned to the goal of reducing the time that occurs between a criminal episode and the referral to community-based treatment services. This reduces the congestion of court dockets for all cases and, for those who are detained pending trial, can reduce average length of stay in custody. Reducing this “time of stay” in jail saves system resources, reduces jail over-crowding, and improves the likelihood of therapeutic engagement. This goal setting will also help to inform program evaluation and research design efforts. System savings and recidivism reduction are also likely goals.

Statutory Authority

Program planners should carefully review whether prosecutors are authorized to create such programs by caselaw, statute, court rule, or by their inherent prosecutorial discretion. In the absence of such authority, program planners may have to initiate an action to create such authority.

Eligibility Standards

Depending on a PLD Behavioral Health program’s eligibility standards, an individual’s prior criminal history, in conjunction with their treatment history, amenability to treatment, and whether a treatment plan can reduce the likelihood of further criminal behavior may need to be considered. Prior threats and the nature and circumstances of the current offense and past offences may also be considered. Eligibility may also hinge on the results of a validated risk and needs assessment. Numerous such tools exist, including tools developed to be gender-specific.

Care should be taken to craft standards that do not disproportionality exclude persons of racial, ethnic, gender, or other vulnerable populations, unless a program is specifically designed to meet the needs of a specialized population.

Treatment Providers

Behavioral health treatment providers generally work in a highly regulated industry. Program planners should pay particular attention to ensuring that all such providers meet state licensing and accreditation standards and demonstrate a commitment to national professional standards both as an agency and as individual providers. Memorandums of Understanding and provider contracts should require compliance with such standards.

Candidate Screening

Because of the complexities of behavioral health issues, it is particularly important that specialized prosecutors are involved in the process of screening potential candidates. Such prosecutors should be trained on behavioral health needs, be thoroughly familiar with the eligibility standards for any diversion options available, and be available to make decisions for both in-custody and out-of-custody defendants. Prosecutors who are already involved in an existing specialty court effort are an excellent resource to screen candidates.

Setting Treatment Conditions

Diversion from the criminal justice system always involves the joint questions of “diversion to what” and “diversion to where”. Treatment plans identify what the course of treatment will be, how long it will take, and who will provide it. Where possible, treatment plans should be developed based upon findings generated from validated risk and needs assessment tools and should address criminogenic risks. It is also necessary to develop a mechanism to monitor compliance with the plan, address violations, and make adjustments to the plan if circumstances warrant a change. A plan is not adequate unless it is reasonably calculated to ensure treatment success and public safety.

Developing an Evaluation Plan

In order to show that these programs can be safe and effective, it is more important than ever to develop a sound evaluation plan when starting such a program. A plan should start with a detailed logic model of program goals and objectives, inputs and outputs, and expected outcomes. Process measures should track program activities and outcome measures should gauge goal attainment. Data elements should also include information on race, ethnicity, gender, and other vulnerable group status, so that impacts on vulnerable populations can be assessed. A research partner with behavioral health and criminal justice system expertise is preferred.

As indicated earlier, special attention should be paid to developing a plan that could be used to establish that recidivism, average length of stay in jail, and time to treatment engagement are reduced, and that cost savings result. Such a plan can be an important strategy to ensure the sustainability of your program.

For more information on developing strong researcher-practitioner partnerships, see the video:

Transforming Criminal Justice through Research and Innovation

For assistance with developing process measures, see:

Process Measures at the Interface Between the Justice and Behavioral Health Systems

For more on information on ensuring sustainability of your program, see:

Developing a Problem-Solving Justice Continuum

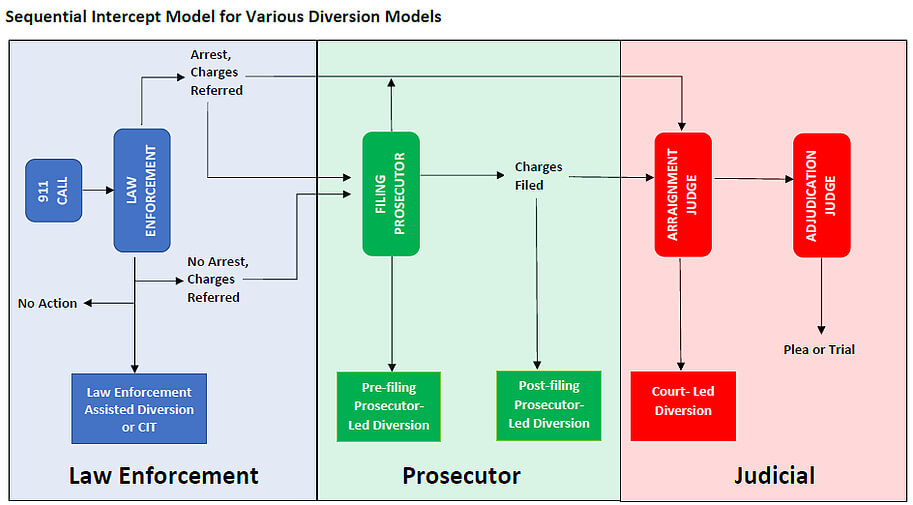

A final matter worth considering is how such a behavioral health prosecutor-led diversion “fits” within the context of a problem-solving justice continuum. Such a program could successfully function in isolation, but there are benefits to seeing it as part of a broader paradigm shift where criminal justice problem solving occurs at each intercept along the Sequential Intercept Model.

Diversion decisions (Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion or Crisis Intervention Team Referrals) could be made by police officers at the point of contact assuming that adequate information exists at the time to a make a sound decision. If adequate information was unavailable, it could be made at the next intercept by jail screeners, at the next intercept by prosecutors, either pre or post-filing, or by the court or pretrial services staff with a referral to a mental health court.

Such a continuum of problem-solving justice could permit the sharing of resources and lead to the more effective triaging of defendants who present with behavioral health issues.

For more information on this intriguing possibility, see:

Behavioral Health Diversion Interventions: Moving from Individual Programs to a System Wide Strategy

See also:

FAQs: A Look Into Court Based Behavioral Health Interventions