Glossary of Terms

Introduction

Retail theft diversion and deflection programs offer prosecutors a unique and powerful tool to address a persistent challenge in communities across the country. These programs provide an opportunity to strengthen partnerships with retailers, ranging from large national chains to small local businesses, by working collaboratively to reduce shrinkage and support safer, more sustainable local economies.

At the same time, these programs create a meaningful pathway for individuals involved in retail theft to avoid deeper justice system involvement and access the support needed to change course. By focusing on accountability, problem-solving, and service connection, prosecutors can help participants move forward, improving individual outcomes and contributing to broader community well-being.

Planning a prosecutor-led deflection or diversion program for retail theft involves a multifaceted approach that requires careful coordination and collaboration across key stakeholders. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for developing and implementing such a program, focusing on essential components such as conceptual development, research partnerships, eligibility criteria, program conditions, team building, participant screening, restorative justice mandates, and therapeutic mandates. By addressing these elements, the program aims to offer an effective alternative to prosecution, address the root causes of the underlying theft, reduce recidivism, mitigate shrinkage, alleviate the burden on the criminal justice system, and provide meaningful support to participants. It is important to note that every jurisdiction has unique resources and varying levels of stakeholder involvement. Therefore, it is essential to tailor the recommendations provided in this guide to meet the specific needs and circumstances of your jurisdiction.

1. Develop a Concept

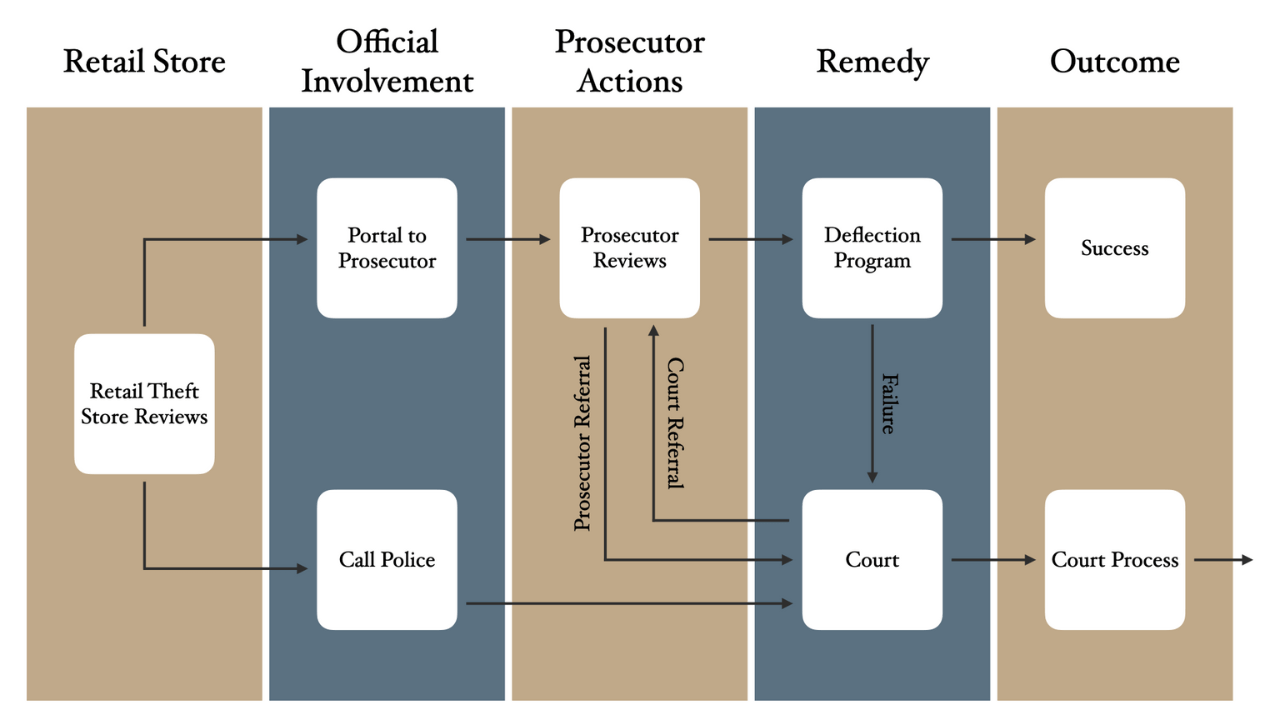

The first step in planning a deflection or diversion program is determining when the program will begin within the case process. Start by assessing the level of involvement and capacity of your law enforcement partners. Understanding this will also help you determine the role of the retail establishment. Questions to consider include:

- Are law enforcement officers committed to making arrests?

- Will they assist in gathering evidence and completing the necessary paperwork?

- Can they support identification through fingerprinting?

Next, determine the level of commitment and capacity of your retail establishments. The more involved law enforcement is, the less responsibility will fall on retailers. However, retailers need a clear understanding of what will be expected of them. Consider the following questions:

- Will they be responsible for detaining the individual until police arrive?

- Are they expected to verify the value of stolen items using receipts or inventory systems?

- Should they photograph the items taken?

- Will they need to complete incident reports or other documentation?

Clear communication of these expectations will ensure that retailers are prepared to effectively participate in the program.

Referral to the Prosecutor

Whether the referral comes from law enforcement or the retail establishment, directing it to the prosecutor’s office allows the prosecutor to review the case before charges are formally filed. At this stage, the prosecutor can choose to divert or dismiss the case, preventing it from entering the court docket. This approach can streamline the process and accelerate the participant’s entry into the program.

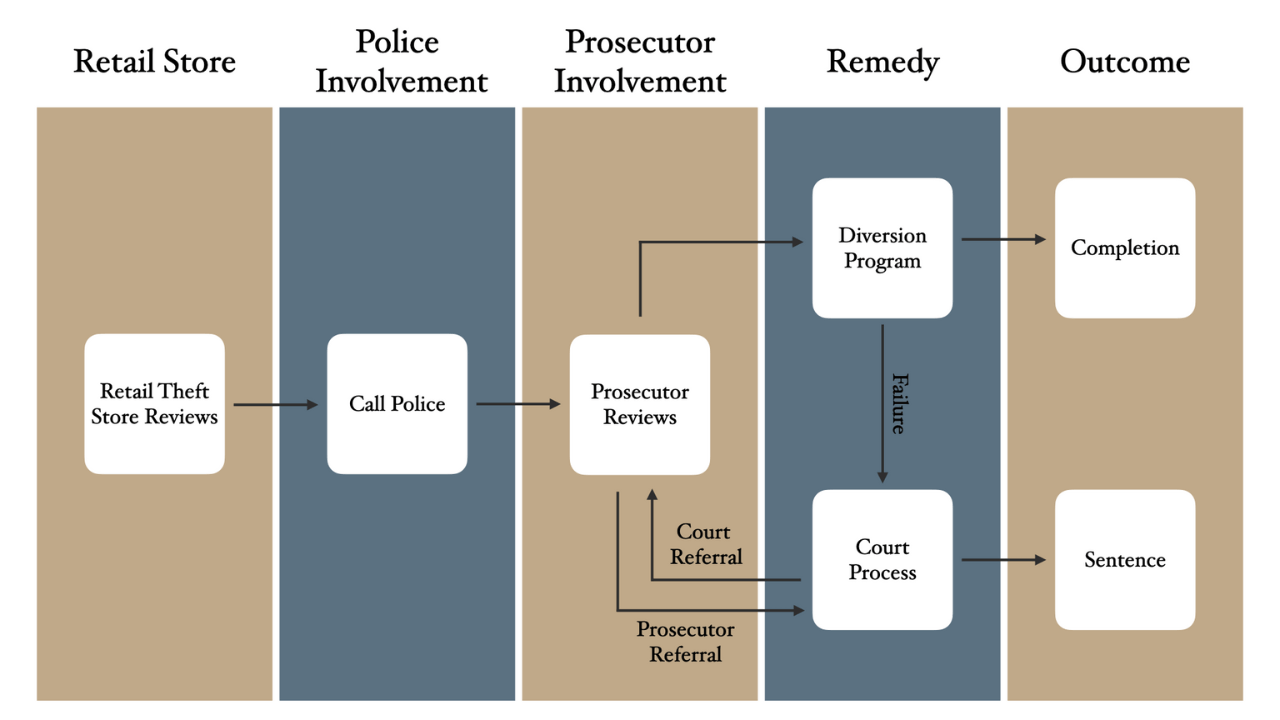

Referral to Court

Once a case is in court, both the defense attorney and the judge may have a role to play. There may be the authority of the court involved as well as additional time for the prosecutor’s role. For the participant, there is a delay to join the program and receive services.

Remember to follow all applicable laws regarding victim notification and victim rights throughout the prosecution process.

2. Engage a Research Partner

Your research partner, drawn from a local school, university or data management position, can help set up your program. They can assist in establishing a baseline using historical data, standardizing the admission process, and developing a methodology to make data measurable and useful. Based on their analysis, they may also identify gaps in available services or suggest adjustments to better meet participant needs.

Your research partner can also help define and measure program success, including both long-term and short-term outcomes. This may involve reviewing entrance and exit questionnaires administered to the participants, talking to your team members, and analyzing the data you collected.

It is important to map out what your research partner needs before beginning the program so that the appropriate data is collected. You will need to define success measures and then determine a time frame for measurement. Many programs track outcomes two to three years after program completion to assess impact.

Following the data can strengthen your program and support continuous improvement. Thoughtful data collection and analysis can also position your program for future funding opportunities. Insights from a research partner can provide a more structured and credible complement to anecdotal information, helping to convey the program’s impact effectively.

3. Crafting Eligibility Criteria

Deciding whom to admit into the program is a critical step. Your office’s goals, the availability of community services, and the strength of your partnerships can help to point the way to the most effective program reflecting your objectives.

Allowing first-time or young offenders can potentially deter these offenders from committing retail theft or other crimes in the future.[i] Limiting justice involvement for these participants can ease caseloads, resource system strain, and contribute to broader public safety goals.[ii]

Programs targeting this population may see a relatively large number of participants but lower overall service needs. Consequently, participants may not need lengthy or deep involvement with multiple services, or a lengthy period of diversion or deflection.[iii]

Programs that serve people with prior system involvement, repeat offenses, or those facing serious life challenges may serve fewer participants—but those participants often need long-term, intensive support.

Common needs may include:

- Mental health care

- Access to food, housing, or clothing

- Employment assistance

- Substance use treatment

But the payoff?

Life-changing outcomes for individuals—and a measurable reduction in overall crime.

4. Create Program Conditions

Program conditions should be thoughtfully designed to reflect the goals of your office. The conditions you require can be based on the level of seriousness of the retail theft committed, the type of participant you are concentrating on, or a combination of both. It’s important that requirements are meaningful—but not so burdensome that participants are discouraged from engaging. If the program feels more difficult than simply pleading guilty, participants may opt out of the program, even if it means having a criminal record.

You can be creative in designing your program conditions. For example, if your focus is on unhoused individuals, consider establishing informal courts with judges in nearby parks, or easily accessible buildings. Meeting people where they are can improve participation and outcomes, making your program more successful. In some cases, people who have not been arrested or flagged for retail theft may also hear about the program and voluntarily seek help, making your approach both proactive and preventative.

Typical program conditions may include:

- Avoiding new arrests or criminal activity

- Paying restitution

- Remaining substance-free

- Participating in mental health or substance use counseling

- Attending community panels or educational sessions

It is important that participants understand the research partner’s role and that data collection is clearly explained.

Providing incentives is key to encouraging participation. Examples of incentives may include services to assist the participant, expungement or sealing of the arrest, access to clothing or food. Equally important is establishing clear consequences for non-compliance, such as referral back to court, additional program requirements, or ineligibility for future diversion or deflection opportunities.

Successful completion should be acknowledged. Whether it’s a certificate of completion, a formal letter from the court, or even personal recognition from a judge, celebrating participants' progress reinforces positive outcomes and strengthens program credibility.

5. Building Your Project Team

One of the most important components of your program is establishing the right team. The strength and commitment of your partners will directly influence your program’s impact. Establishing written goals can produce unity and confidence in the program, as long as every team member is informed of the goals and has the opportunity to provide input.[iv]

In addition to shared goals, it is equally important to define the process. Your partners will need a clear understanding of their roles and responsibilities within the program. Developing a caseflow document that lays out each step of the process can help clarify where each team member fits.[v] Make sure you seek input. Your team may think of things you do not or have a new perspective that you did not know that you needed. Distributing both the goals and caseflow to all your team members will reinforce that they are a part of something. It also will reiterate the practical aspects of who does what.[vi]

A sample caseflow may look like:

You should designate someone from your own office to lead the team. That prosecutor must have the authority to make decisions that the rest of the team can rely upon.

In addition to your prosecutor lead, you will need to have a community or system partner who can evaluate the participants’ needs. Depending upon your decision making, the person may also perform risk assessments, make referrals to services, or complete any entrance questionnaire required by your program. This person may also serve as the “navigator” for the participant in the program.[vii]

A member of law enforcement should be a part of the team. Even if programs do not rely on an arrest at the outset, law enforcement may be called upon to determine a person’s identity, help execute a warrant or provide transportation.

In some models, the retail establishment may conduct its own investigation. This can include tallying seized items to determine value, photographing evidence, and writing reports. Law enforcement involvement may be limited to verifying the individual’s identity and criminal history or providing transportation. Early and intentional engagement with law enforcement is essential. Meet with them to explain the goals of the initiative, understand the jurisdiction’s needs and constraints, and work together to define when their involvement is necessary. Recognizing their limited resources helps build trust—so when a call does come in, from either the prosecutor or the retailer, law enforcement will know that the call is very important. Once the investigation is complete, the retailer can file cases directly with the prosecutor’s or clerk’s office, either in person or through an online case management system or portal.

If law enforcement is going to assume a significant role, they often gather the evidence, complete the investigation, interview witnesses, and write reports. They may also make a referral for the program directly to the prosecutor’s office or a community navigator. The navigator can then engage the participant immediately and connect them with needed services. This pre-filing referral can bypass the need to come to court, allowing for the fastest potential pathway into the program and quicker access to support participants.

Finally, it is important for your team to meet regularly. Communication, referrals, and addressing participant issues should be clearly described. Written protocols, MOU, and clarifying documents can help clarify roles and support effective collaboration.[viii]

6. Participant Screening Process

The participant screening process may vary depending upon whether the individual is in custody or out of custody. It is strongly recommended that either the prosecutor’s office or one of your partners screen the potential participant before admitting them into the program. Where appropriate, the screening should be a requirement for admissions.

Screening may include a risk assessment, tailored to fit your program’s structure and target population. It may be a fully developed risk assessment or a simplified version that meets your jurisdiction's capacity and needs. The screening should be documented and geared towards the type of participant you want to focus on.

For programs focused on individuals with prior justice system involvement, screening can help identify factors that may impact program participation, for example, restrictions on proximity to schools or designated safety zones. In these cases, a basic risk assessment may be necessary to protect community partners and ensure appropriate service placement. For a program focusing on first time or juvenile offenders, a risk assessment may not be required.

Your program may also establish different conditions based on participant age. For example:

- Youth participants may be required to engage in mentorship, attend school regularly, or meet specific educational goals.

- Adult participants may be referred to job training, parenting support, or other life skills programs.

Finally, it is important that you either direct or assist the participant on how to seal or expunge their record if they complete the program successfully. Each state has different laws or requirements for either sealing or expungement.

7. Developing Therapeutic Mandates

To address the root causes that may contribute to retail theft, integrating therapeutic support into your program can be a powerful tool for long-term change. When appropriate, counseling services—particularly related to substance use, trauma, or behavioral health—can play a key role in reducing recidivism and supporting participant stability.[ix] Depending on the severity of the issue, this may include inpatient treatment, outpatient counseling, peer support groups, or regular check-ins combined with random drug testing. Your navigator or program partners should be equipped to assess each participant’s needs and recommend the most appropriate treatment plan.

Cognitive, behavioral or trauma-based therapy may be helpful for some of your participants, especially those with more extensive criminal backgrounds.[x] Therapy can be offered individually or in group settings, and in some cases, couples or family therapy may help support broader healing and behavior change.[xi] For participants with first time offenses, counseling may not be necessary.

8. Create Evaluation Plan

Knowing whether your program works is arguably as important as having the program itself. If you are looking to expand, or to apply for funding, performance measures may be essential. While anecdotal evidence has value, documented numbers are the standard to work towards.

Establishing a strong partnership with a researcher is a foundational step. Your partner may come from a local school or research group, or from a remote location. As long as you can share necessary data securely and meet regularly, distance is not a barrier. The earlier that you involve your research partner in your planning stages, the better. They can help to define success measures, design evaluation tools, and develop clear methods for tracking and presenting outcomes.

One way of measuring effectiveness is recidivism. You will need to define the parameters of recidivism. It may be statutory or not. If the definition is not statutory, defining recidivism should include:

- The time frame for tracking outcomes (e.g., 12, 24, or 36 months post-program)

- What constitutes a new offense (e.g., arrest vs. conviction)

- Whether only certain offenses count (e.g., retail theft vs. any criminal charge)

- Whether non-criminal violations (e.g., traffic tickets or citations) are included

Whatever success looks like for this program, ensure that its definition is shaped not only by input from your office, the retailer, law enforcement, and other branches of the criminal justice system, but also by meaningful contributions from the community and individuals with lived experience.

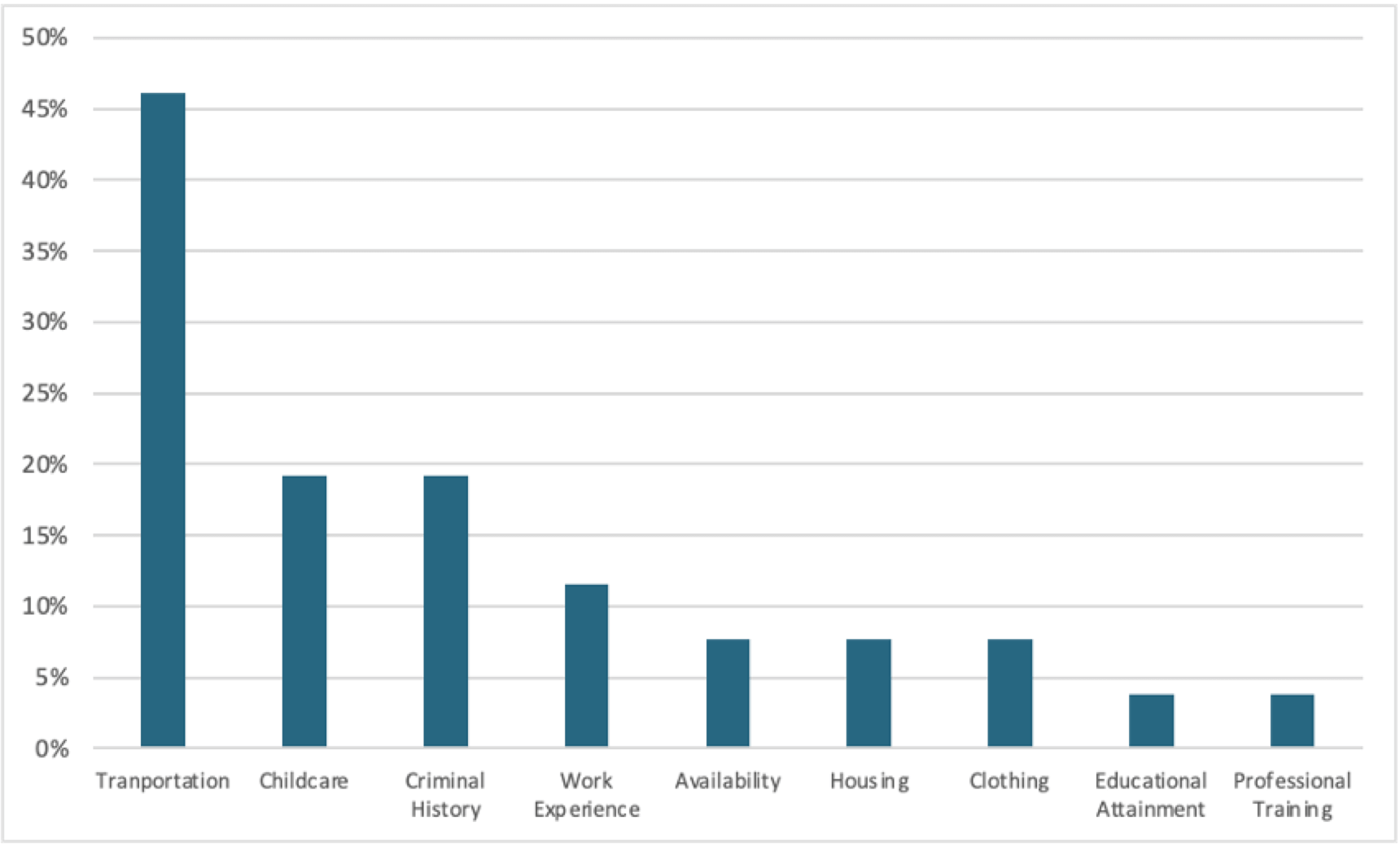

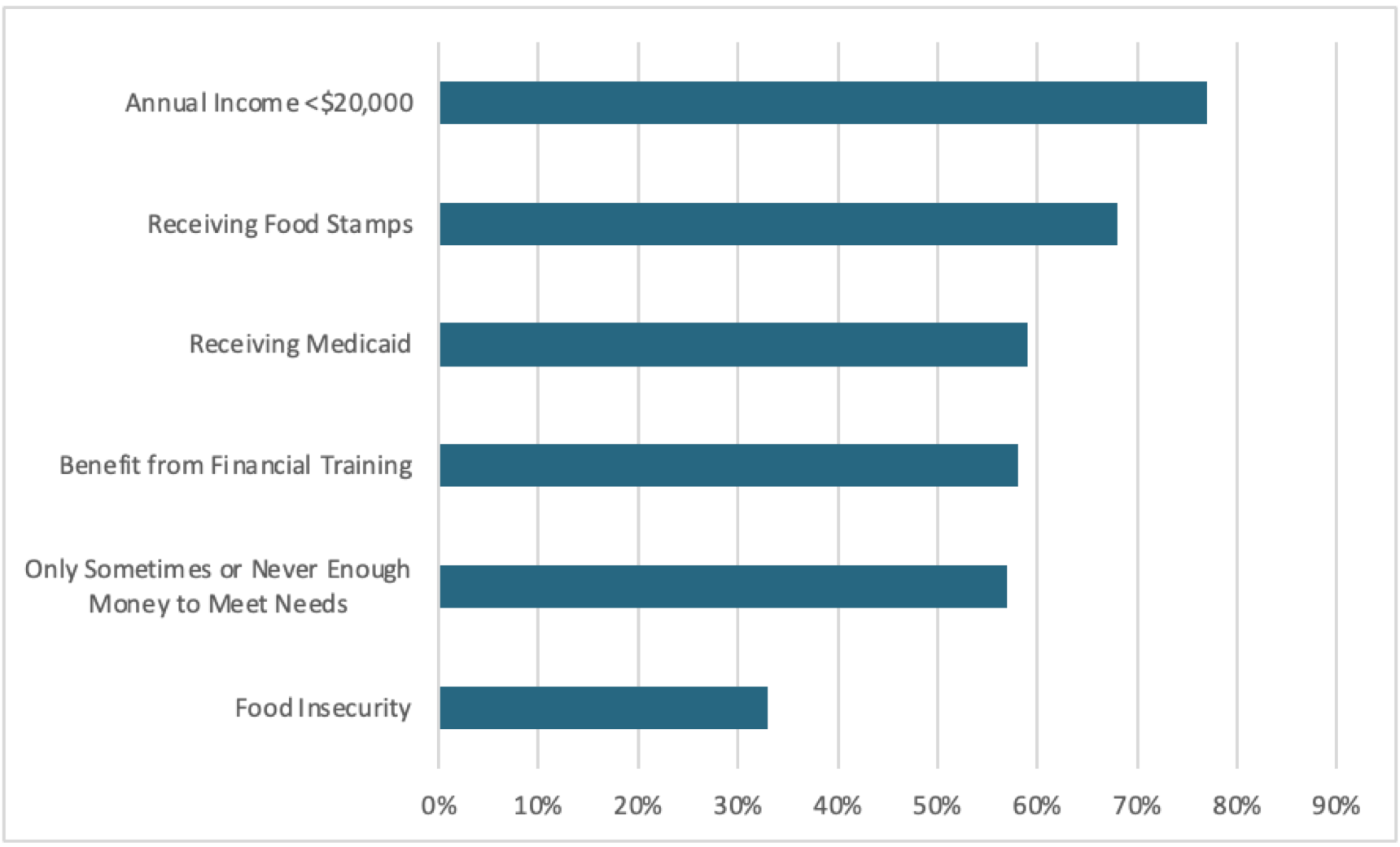

In retail theft, many of the participants face significant life challenges. Conducting an entry questionnaire[xii] and an exit questionnaire[xiii] may be a way to measure micro changes in the participant’s life. The questionnaire may include their needs. These can include questions about:

- Housing stability

- Access to food and clothing

- Employment status

- Childcare needs

- Substance use or mental health needs

By comparing responses at program entry and exit, your team and research partner can identify micro-level changes and areas of impact. Including open-ended questions also gives participants a voice in shaping future program improvements and ensures the program remains responsive to real-world needs.

9. Modeling the Program

Begin with a limited number of cases to pilot the program. Incorporating a phased rollout into your planning and team meetings allows for controlled testing, learning, and adaptation. Starting small helps identify operational issues early, before they affect a larger caseload.

As you begin to roll out your program, you may encounter some challenges. These may include:

- Incomplete or delayed data sharing with your research partner

- Limited treatment provider capacity

- Insufficient referral options from your navigator or community partners

Use these early experiences to refine your processes. Adjustments made during the initial phase will help strengthen the program’s foundation.

You will need to monitor the program as you expand. Track key metrics such as participant volume, completion rates, and service utilization. If you find that too few or too many individuals are entering the program—or that participants are struggling to succeed—it may be time to reassess eligibility criteria, program conditions, or service availability.

No matter where you are in your program, it is important to pivot if necessary. Your partners can be invaluable in helping you to decide what changes are good, how to enact them, and when. Though the final decision may be yours as the office running the program, your partners bring you perspectives, knowledge and skill that you may not have.

Retailers are critical stakeholders. Look for ways to make participation easy and meaningful. For example, if filing complaints through a portal is easier, encourage the retailers to do so. It is strongly recommended that you meet with a committee of your retailers at least twice a year. These meetings provide an opportunity to:

- Share key program data and outcomes

- Reinforce transparency and trust

- Gather feedback on successes, challenges, and opportunities for improvement

This transparency and open dialogue not only strengthens buy-in but also helps identify new strategies for expanding and enhancing your program.

Final Thoughts

As you consider launching or refining your prosecutor-led deflection or diversion program, remember that you’re not starting from scratch. Across the country, jurisdictions have piloted innovative approaches, navigated challenges, and built strong partnerships to support participants and reduce retail theft. If you’re looking for inspiration, practical tools, or even a design partner, the Association of Prosecuting Attorneys (APA) has collaborated with offices nationwide to develop tailored solutions and share lessons learned. Explore APA’s growing library of resources and connect with peers who have walked this path—your next step might be easier than you think.